Men•tal Ill•ness (Noun)

Last week, we talked about the basic premises of mental health. Mental illness, however, is different. It’s common for people to use “poor” mental health and mental illness interchangeably, but they’re not the same.

- If you’re my mother, mental illness is the result of not praying enough.

- If you’re the media, mental illness is the thing that bars deranged white men who open fire on sweet old people at church or cute little kids at school from being held accountable and going to prison for their very intentional actions.

- If you’re the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders., 5th ed. (DSM-5), mental illness is, “a syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or developmental processes underlying mental functioning.”

I’m not in the slightest trying to tell you what definition of the word you should go with, as that would be rather BOLD of me. However, the DSM-5 is a book published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) that contains all of the clinically-recognized mental disorders in the Western world, as well as criteria for diagnosing them and a bunch of other relevant science-y stuff. Within its pages, you’ll find conditions on the more common side, like depression, schizophrenia, and anxiety. You’ll also find Alien Hand Syndrome, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, and Clinical Lycanthropy. Essentially, it’s the therapist bible, and although there is much debate about its usefulness (this is a discussion for another day), it’s as legit as legit gets. And no matter how you spin it, mental illness is real, and it’s a b*tch.

Note 1: While mental health relies more on value judgments regarding what’s healthy, what’s normal, and what’s most important, the presence of mental illness or a mental disorder is marked by a diagnosis, definable and measurable symptoms, a significant level of distress/impairment that affects multiple aspects of one’s life, and an increased risk of self-harm/suicide.

Note 2: Mental health and mental illness can be concurrent, or exist simultaneously. This means someone can be on the lower end of the mental health continuum without meeting criteria for a mental illness. And likewise, someone who meets criteria for/has been diagnosed with a mental illness can have episodes where their mental health enables them to function and adjust well to stressors in their life.

Where Does It Come From?

So how does one find themselves with a mental disorder? I’d love to say the origins are clear and stem from listening to the musings of Andrew Tate, Joe Rogan, Kevin Samuels, or just toxic men (with or without podcasts) in general, but I’d be lying. In fact, it’s a lot more complicated than that.

In a recent article published by Counseling Today, Theresa Shuck, leading genetics counselor and psychotherapist, states that “genetics, environment, lifestyle and self-care (or lack thereof) all work together to determine if someone will develop a mental disorder.” She is absolutely correct (I say, with my two-thirds of a Master’s degree), but the specifics of how it comes to be, the meat and potatoes the masses are craving, are still relatively unknown. Let’s use the genetics factor, for example. Emily Deans, M.D. of Psychology Today, tells us that:

- Anxiety disorders, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) = 20-45% heritable

- Alcohol use disorder and Anorexia Nervosa = 50-60% heritable

- Bipolar Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASDs), Schizophrenia, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) = 75%+ heritable.

All this data, and still, no singular depression gene, alcoholic allele, or ADHD chromosome!

The truth is that the degree to which these factors exercise their control will differ from person to person, and there’s no set formula to determine how they’ll play out. A line at a party could be a good time for one person and the beginning of a fierce battle with drug-induced psychosis for another. A tour spent in Afghanistan could be a four-year commitment that yields awesome stateside perks for some and lifelong night terror and panic attack fuel for others. A childhood spent coming of age in abject poverty could be the motivating factor behind “making it big” for one person and the motivating factor behind jumping off a bridge for another. We just never know.

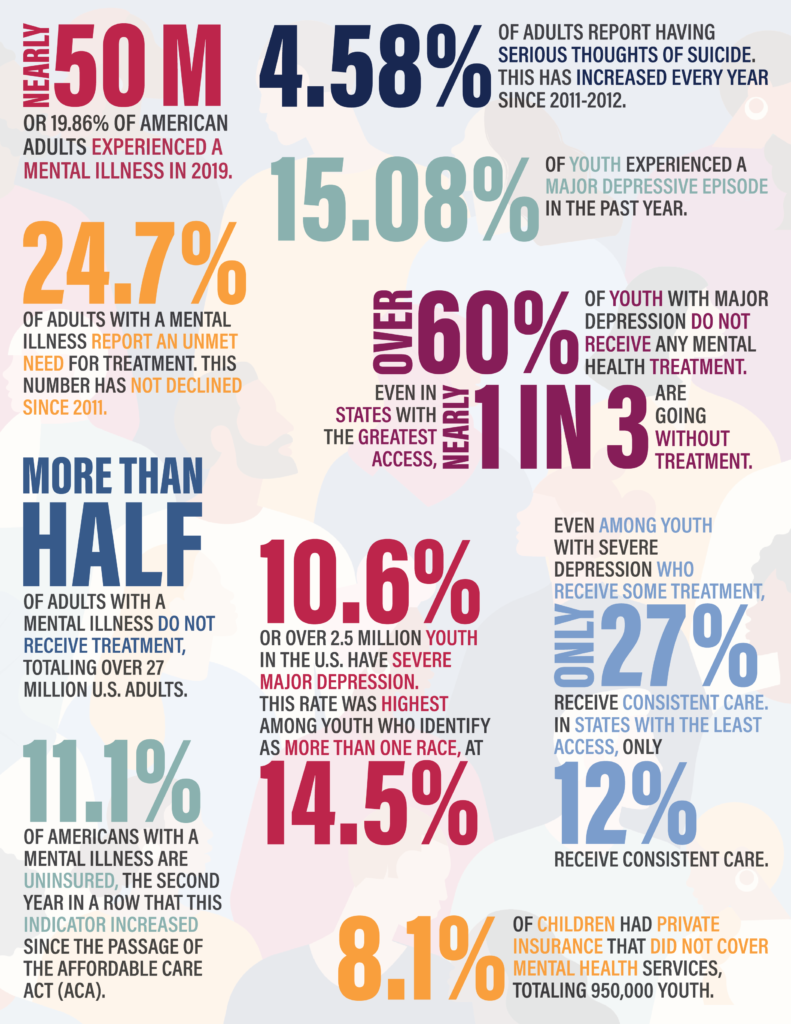

The stigma surrounding mental health certainly doesn’t help either. Chalking mental illness up to a character defect, a result of an overactive imagination, weakness, a lack of willpower, or an excuse to treat someone as subhuman does absolutely NOTHING but push people away from seeking treatment/finding support in community and deeper into the bottomless pit where feelings of shame, guilt, denial, and worthlessness love to reside.

So Where To?

It’s no secret that we have a lot of work to do regarding our approach to mental disorders. I love studying the stuff, and even still, I get discouraged and doubt that there is anything I can really do to make a change. There is still so much to be discovered, so much to categorize, and so much to conceptualize. But my clinical advice in the meantime? Love your neighbor as much as you love yourself. Be kind. Be considerate. Be patient. Be gracious.

Note 3: If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org.

This subject is expansive, and there are still so many aspects of it we’ll explore in the future. For now, prepare to have all (or at least a couple) of your misconceptions about therapy “un-misconceptualized” next week!

From my chair to your screen, Charity